Angus Geology

Experiences varied greatly during the pandemic lockdowns. Some people were able to have daily walks in the countryside and to make the most of the uninterrupted time with nature. Other people were stuck inside, unable to leave their homes.

There was a surge of interest in local geology during the pandemic. People of all ages began to explore and learn about what they had seen throughout their lives yet not truly observed until then. Interesting rocks and stones were noticed and collected during walks along the coastline and through the deep glens between steep hills (including the ten Angus Munros - peaks over 3000 feet). These samples tell us a lot about how Angus came to be. Interest in geology did not fade as we emerged from the pandemic. In 2021 the Scottish Geology Trust held several well attended events across Angus as part of a now annual Geology Festival.

Our Angus Remembers timeline and catalogue of rocks, created by geologist Morag Smith, describes how Angus was formed over millions of years and shows how the rocks we can see around us help to tell that story.

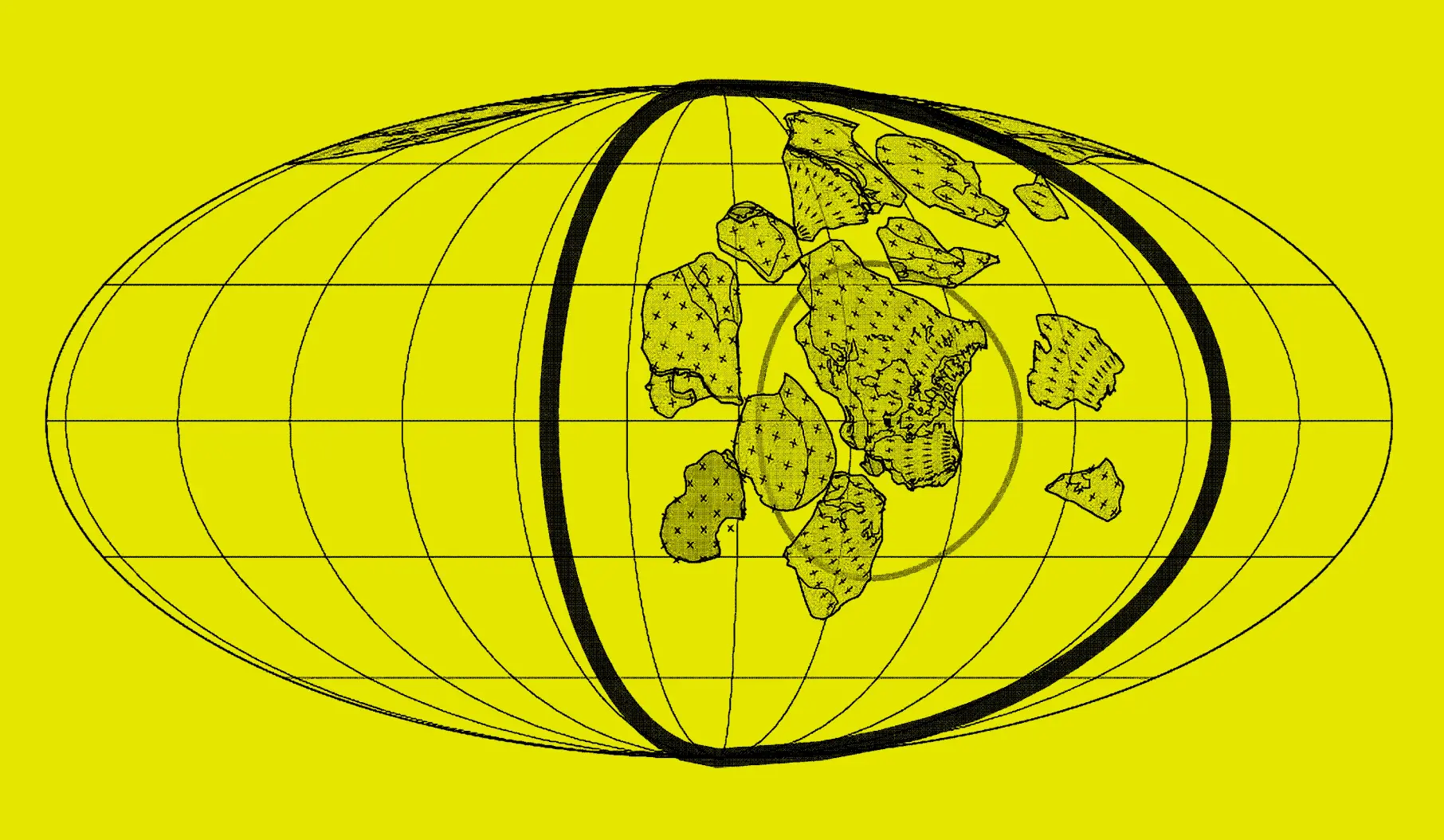

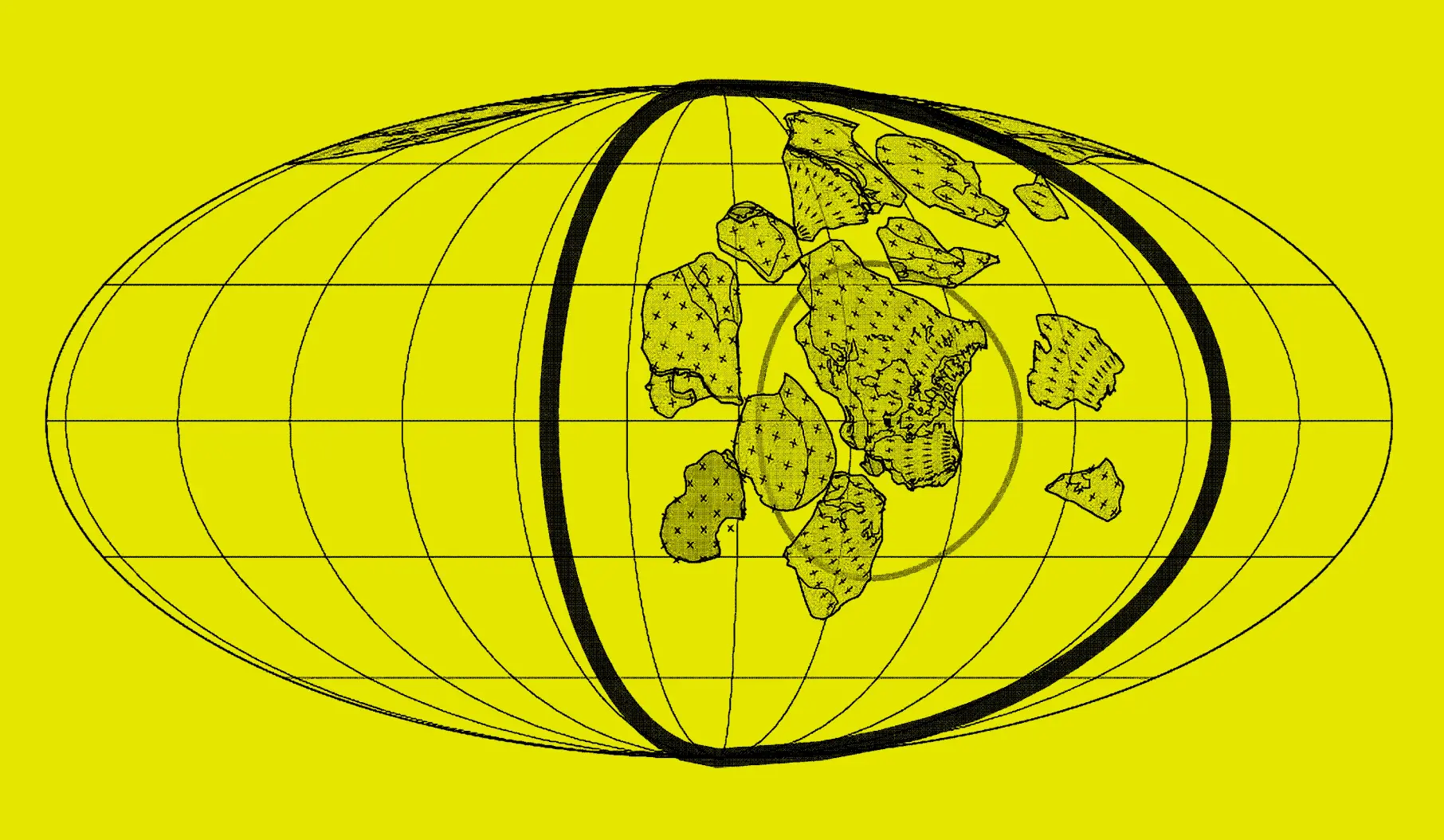

The Supercontinent Rodinia

1.3–1 billion years ago

The supercontinent of Rodinia, containing all the land on earth, had formed around 1.26–0.90 billion years ago. It started to break up around 750 million years ago and a part of Angus was situated in what would later become the continent of Laurentia.

Dalradian

750–470 million years ago

As Rodinia broke apart shallow seas, such as the Iapetus Ocean, formed as the continents separated and many of the rocks seen in the Angus Glens were deposited. The rocks are a sequence of sandstone, siltstone and mudstones collecting in shallow and deep oceans and are known as the Dalradian Supergroup. Scotland at this time was part of a Northern continent called Laurentia, which included Canada (this is why Scotland and Canada share similar geology). England was part of a Southern continent called Avalonia.

Closure of the Iapetus Ocean

490–390 million years ago

Eventually the seas stopped spreading and the great Iapetus ocean between Laurentia and Avalonia started to close up. Around 425Ma the continents collided and the ocean was gone. This is known as the Caledonian Orogeny. From here on in Scotland and England were joined close to where the political boundary is situated today.

Caledonian Orogeny

490–390 million years ago

This is the moment when continents collided and mountains were created. The Midland Valley, which Angus sits within between the Highland Boundary and Southern Uplands Fault, marks the join where Laurentia, Baltica and Avalonia continents collided during the closure of the Iapetus Ocean. This event was the biggest to effect Scotland geologically and is known as the Caledonian Orogeny. A large mountain range formed similar to the Himalayas today. This event created the Scottish Highlands, the Appalachian mountains in North America and similar mountain ranges in Norway, Greenland and Ireland. Within these mountains the Dalradian rocks were folded and twisted into the style we see them throughout the Angus Glens today. Granites were emplaced deep into the mountains during this period and are now visible today in the Cairngorms.

Devonian

419–359 million years ago

Almost immediately the Caledonian mountains began to erode and great continent sized Mississippi style rivers fed the sediment down onto the valley floors. The rocks were tumbled naturally in the rivers creating pebbles and sands which eventually settled and were buried forming the conglomerates, sandstones and mudstones seen in the Old Red Sandstone sequences in Angus. At this time Scotland lay just south of the Equator. The climate was hot and dry, with seasonal rains. Volcanic activity gave rise to extensive lava fields which now host some of the most impressive agates in Britain.

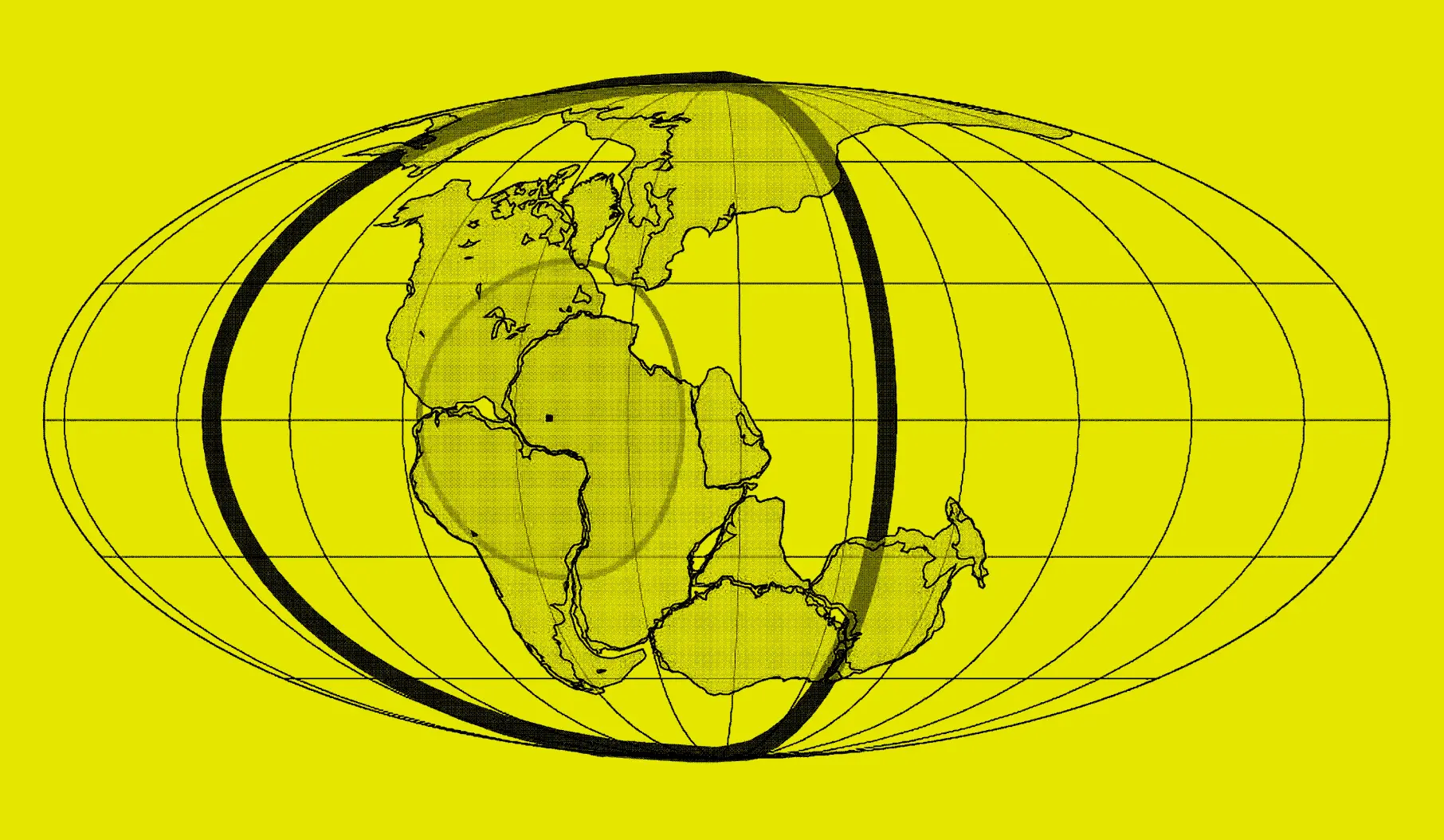

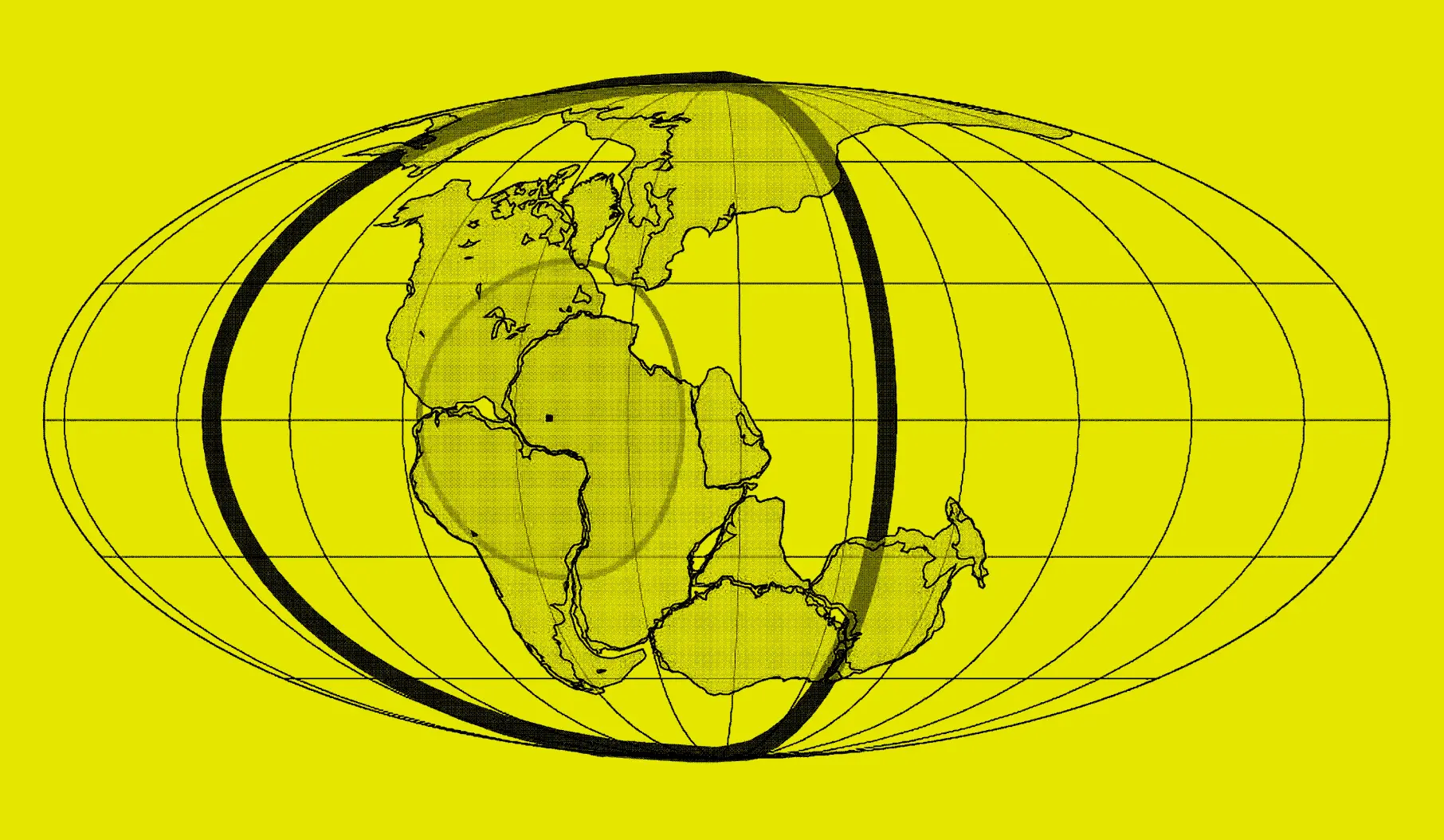

Pangaea

335–200 million years ago

The Caledonian orogeny was part of a process where all the continents came back together to eventually form another global supercontinent called Pangaea. This was the last complete supercontinent on our planet to date and the break up eventually formed the continents as we know them today. When Pangaea formed it squeezed, tilted and gently folded the Angus rocks into the style we see them today.

Volcanism

420–300 million years ago

When Avalonia, Baltica and Laurentia collided together the rocks at depth began to melt and then rose to the surface as volcanic eruptions. Angus was volcanically active for hundreds millions of years and the lavas that erupted are still visible across the landscape producing some of Britain's most stunning agates. These agates occupy the spaces left behind as gas bubbles in the lava flows.

Now you know a bit more about how the Angus landscape was formed, you know about the proof left in rocks. Follow our guide to identify local rocks. Perhaps you could start your own collection. If you’re able to visit a beach, you might find this pebble guide handy: visit the website.